by Lane Chasek

“Postmodern” is one of those words that means nothing because it means so many things. The postmodern concept of the self is one of constant flux. The you of yesterday, today, or next year could all be very different people. Additionally, labels such as “American” or “sane” or “diabetic” collapse into meaninglessness, because what does “American” or “sane” or “diabetic” mean at the end of the day? Everything’s irreducible and/or negatable through a postmodern lens, and postmodernism scoffs at the very concept of definition.

Of course, if you talk to anyone with common sense, postmodernism sounds like the intellectual equivalent of navel gazing only to discover belly button lint, and in many ways, they’re right. It’s not the kind of movement that has wide appeal.

Something I’ve noticed about movements like modernism, realism, and romanticism is that they double as personalities, and are thus easy for people to conceptualize. You can think of anyone you know and easily label them as a hard-nosed modernist, a grim realist, or a wistful romantic. Hell, I’ve encountered people I would call post-colonial. But unless you’re describing someone’s artistic output or area of study, nobody’s a postmodernist.

What is postmodernism, then? As a trait, it’s hard to pin down. As a movement, it’s impossible to find a definition that satisfies. But you know what does satisfy? A nice can of 7Up. Then it hit me—postmodernism is 7Up.

What makes 7Up the most postmodern soda of all time isn’t the fact that no “normal” person enjoys it, though that’s part of the reason. And it isn’t just because it’s overshadowed by Sprite’s bold race consciousness, Mountain Dew’s youth-centered realism, or Sierra Mist’s admirable but ultimately doomed foray into New Sincerity. To truly understand why 7Up is the carbonated epitome of postmodern thought, one must look to its history and what it tried to embody at the height of its popularity.

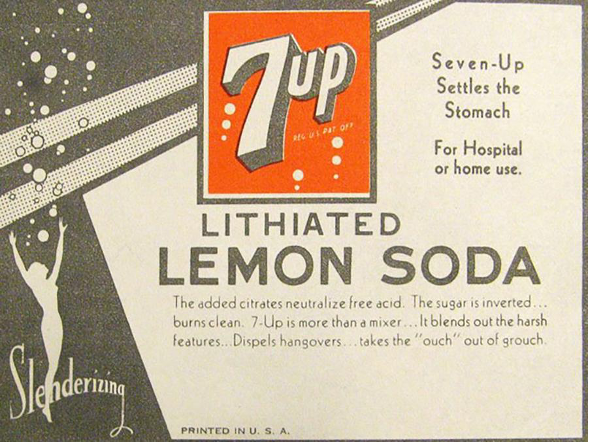

7Up was originally called “7 Up Lithiated Lemon Soda” when it was released in 1929 because it contained the mood stabilizer lithium citrate. Adding psychoactive substances to soft drinks was common practice back then; after all, sodas were sold as medicine rather than sweet treats up until the middle of the 20th century. While art and literature throughout most of human history was created for monetary and/or practical purposes (whether it was painting murals for the Catholic Church or composing odes and epics for the royal family), soda was a purely utilitarian affair.

Up until the late 1960s, 7Up scraped out a meager existence as a hangover cure and vodka mixer. Most products, whether they were shampoos or rat poisons or cheese spreads, lived humble lives during this era. Ads back then were straightforward, text-heavy, and strangely scientific in how they appealed to consumers’ brains rather than their emotions and aesthetic sensibilities. Soda was soda, beer was beer, we knew Head & Shoulders worked because we tested it on rabbits, and nine out of ten doctors agreed that Winston cigarettes were good for you. This was the late modernist era of not just soda, but all mass-produced goods.

But somewhere between the dawn of the Vietnam War and the height of the Civil Rights movement, America experienced a paradigm shift—the Hippie Revolution. On one hand, the hippies were mostly rich white kids who wanted to stick it to Mom and Pop, but on the other hand, they gave birth to a new ethos of visual art and music that was both garish and soft, equal parts political protest and artistic theory. Massive quantities of weed, DMT, LSD, Jacques Derrida, and Marshall McLuhan gestated in the collective minds of the hippies. Practically overnight, postmodernism became mainstream. Class and race distinctions dissolved. Soup cans and comic books became high art. Men could wear their hair long, women could wear it short. Everything and everybody were suddenly “One,” though no one could tell you what “One” meant. Everything meant something, except when everything meant nothing, which still counted as a kind of something. And everything from cars to buildings to hairstyles to shoes were symbols, metonyms, or synecdoches for something else.

7Up had an idea—become the soda of the Hippie Revolution. In other words, become the first postmodern American soft drink.

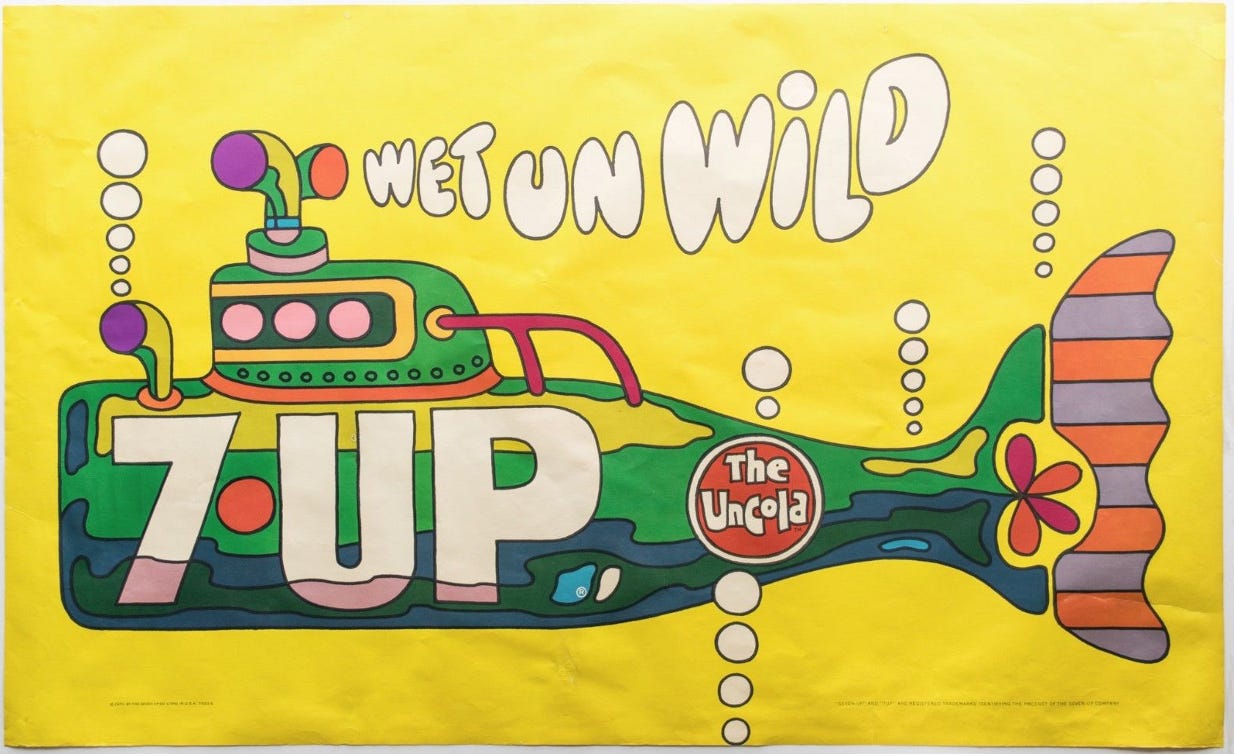

Psychedelic 7Up ads popped up all across the country at the height of the Flower Power craze and well into the 70s (billboards, murals, magazine centerfolds, etc.). It was a desperate appeal to the minds and wallets of people who weren’t always thinking clearly and often didn’t believe in money, but somehow, 7Up sales skyrocketed.

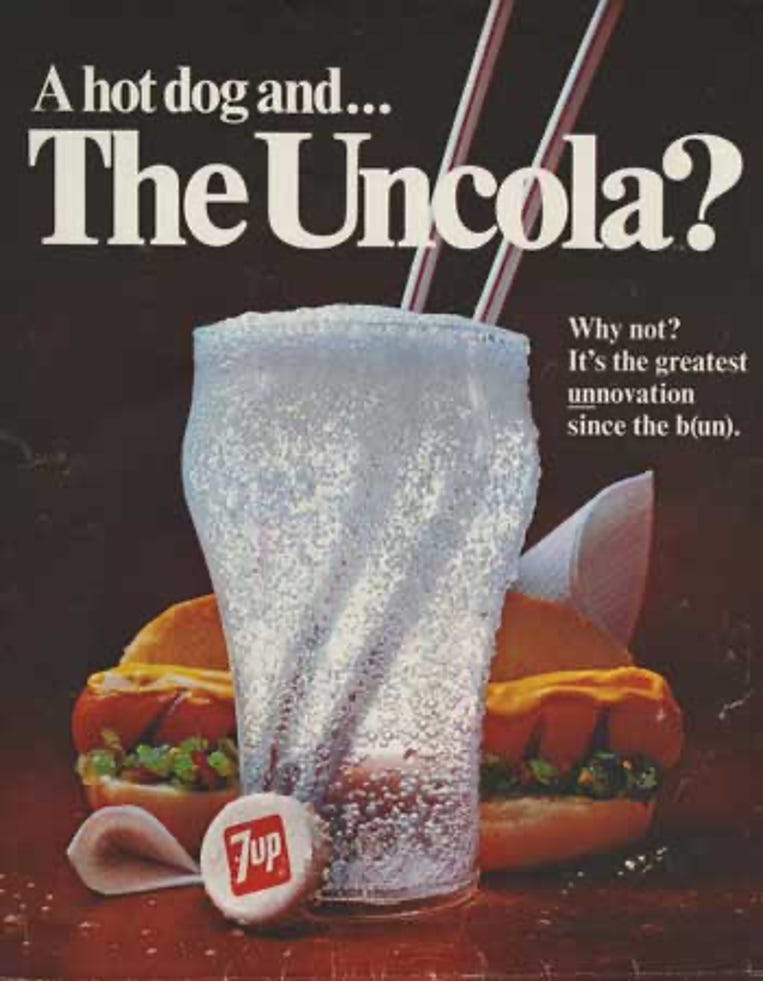

Adding fuel to the patchouli-scented fire was 7Up’s new slogan and identity: The Uncola. At a time when colas were the top sellers in America’s soft drink market, 7Up doubled down not on what it was, but rather on what it wasn’t. 7Up was colorless. 7Up had no caffeine. 7Up wasn’t a symbol of American imperialism like Coca-Cola, nor was it a symbol of materialistic youth culture like Pepsi. 7Up was unknowable, yet at the same time all-powerful and all-loving. At the heart of this new un-identity was the negating prefix un-.

If Derrida designed an ad campaign, it would be The Uncola. This via negativa of brand identity not only emphasized 7Up as a material product you could crack open and enjoy, it also defamiliarized the viewer with the very concept of advertisement and what an ad is supposed to communicate. These are ads that are aware of being ads, ads that are aware of being perceived and evaluated as ads, ads that break the mold while still keeping it intact. If I were to ever teach a class on postmodernism, I wouldn’t force my students to read Roland Barthes essays. Instead, I’d show them 7Up ads and serve them 7Up in tall, frosty glasses.

On one level, these ads seem cynical and needlessly heady, but it would be hard to exaggerate how effective they were. Though most people these days think of 7Up as that other lemon-lime soda that isn’t Sprite, there’s still a cadre of former hippies who drink it (as the grandson of some of these former hippies, I would know). Up until the 80s, 7Up was the third best-selling soda in the U.S., a surprise crystalline contender that managed to keep pace with big dogs like Coca-Cola and Pepsi.

But the 80s onward weren’t kind to 7Up. Just as postmodernism fell out of vogue toward the end of the 20th century when such movements as third-wave feminism, post-colonialism, and post-postmodernism were gaining popularity, 7Up found itself losing relevancy in a post-Flower Power world. The diet and zero-sugar sodas that flooded the market throughout the 80s made 7Up’s past claims of being a “healthy” soda seem ridiculous in hindsight. Then, in the late 80s, 7Up launched 7Up Gold, a cola-like concoction that contained caffeine. For a brand that had flaunted its caffeine-free status for decades, this was a baffling (not to mention hypocritical) move. 7Up had, sadly, sold out everything it had ever stood for.

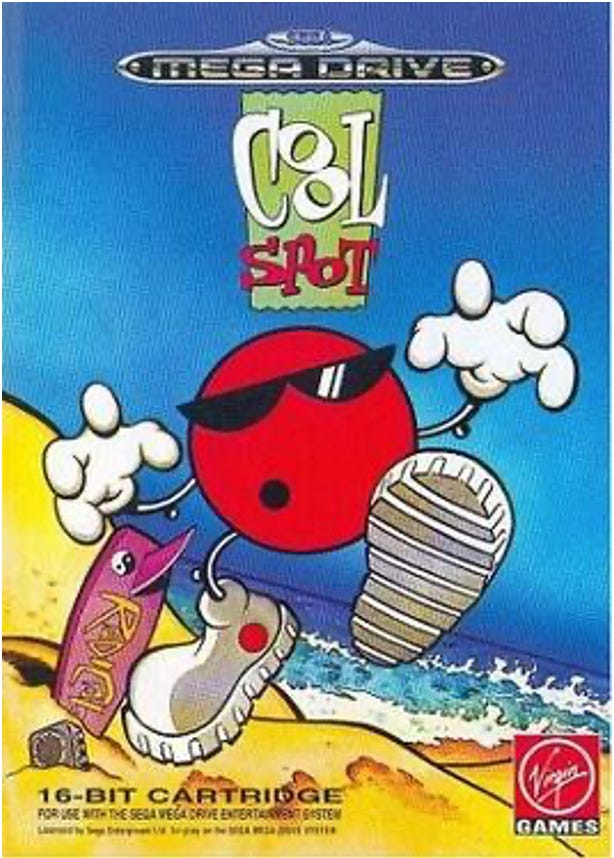

The 90s found 7Up attempting to adopt that decade’s brand of cool, resulting in such products as the video game Cool Spot, a platformer starring the hip, shades-wearin’ red dot from the 7Up logo, as well as a series of commercials in which Orlando Jones spouted such catchphrases as “Up yours!” and “Show me your cans!” Unlike the crisp, refreshing taste of 7Up, these attempts at recapturing the market were short-lived and left a bad taste in everyone’s mouth. For lack of a better word, this period of 7Up’s history was cringe.

Today, 7Up is a pathetic shadow of its former self. It went from the antithesis of the military-industrial complex to the soda you give your kids when they have the stomach flu. But that just makes 7Up more postmodern and, to me at least, more admirable. Like the postmodern self, 7Up has lived in constant flux, evolving with the times while maintaining its identity as the soda without an identity.

So the next time you and your hipster friends get on the subject of postmodernism, tell them to shut their mouths. Reach into your fridge and pull out some frosty cans of 7Up for them to enjoy and educate themselves with. And if they ask if you have Sprite or beer or a Thomas Pynchon novel on-hand, find new friends. They don’t deserve you, and they certainly don’t deserve the timeless flavor of 7Up.

Lane Chasek (@LChasek) is the author of the nonfiction book Hugo Ball and the Fate of the Universe, the poetry/prose collection A Cat is not a Dog, and two forthcoming chapbooks, Dad During Deer Season and this is why I can't have nice things. Lane's current pride and joy is an essay he published in Hobart about Lola Bunny and the latest Space Jam movie.

Can’t wait to read your article on post-post-modernism--this was hilarious!!! Thank you!